This section provides a review of linear algebra concepts, particularly the matrix formulation of simultaneous equations, which you will have encountered in Engineering Mathematics.

A system of linear equations consists of simultaneous equations where the unknown variables appear as linear combinations. A common application of linear systems is curve fitting, such as determining the equation of a straight line that passes through given data points.

Fitting a Straight Line Between two Points

Consider two data points: \((x_1, y_1)\) and \((x_2, y_2)\). We want to find the equation of the straight line that passes through both points. From the equation of a straight line \(y = m x + c\), we can form a series of simultaneous equations from our two data points

\[\begin{aligned} y_1 &= m x_1 + c \\\ y_2 &= m x_2 + c \end{aligned}\]which can be written in matrix form as

\[\begin{aligned} \begin{bmatrix} y_1 \\ y_2 \end{bmatrix} &= \begin{bmatrix} x_1 & 1 \\ x_2 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} m \\ c \end{bmatrix} \\ \mathbf{y} &= \mathbf{A}\mathbf{x} \end{aligned}\]To find the vector \(\mathbf{x}\) we need to solve this system, which is done by pre-multiplying the equation by the inverse of matrix \(\mathbf{A}\):

\[\begin{aligned} \mathbf{A}^{-1}\mathbf{y} &= \mathbf{A}^{-1}\mathbf{A}\mathbf{x} \\ \mathbf{A}^{-1}\mathbf{y} &= \mathbf{I}\mathbf{x} \\ \mathbf{A}^{-1}\mathbf{y} &= \mathbf{x} \end{aligned}\]where \(I\) is the identity matrix. Remember that we can only invert the matrix if it is square (if the number of equations equals number of unknowns), as it is here.

In MATLAB the inverse can be calculated using the function inv - e.g.

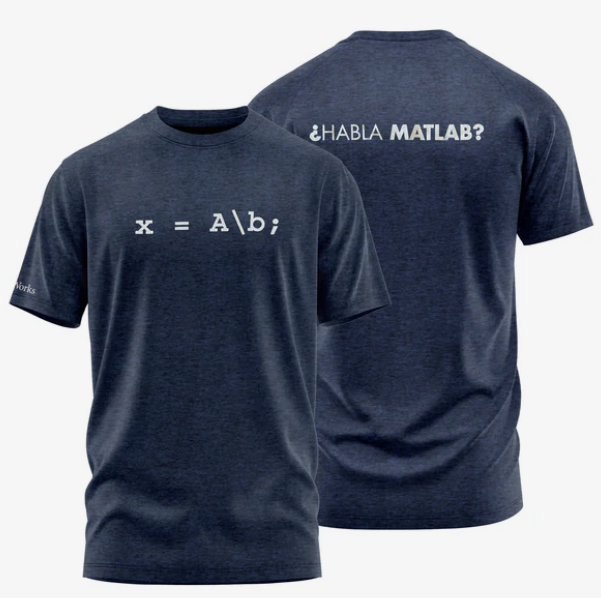

A_inv = inv(A);. However, calculating the inverse of a matrix numerically is a costly operation that can also introduce numerical instabilities into your operations. Instead the vector \(\mathbf{x}\) can be calculated using the inbuilt MATLAB function mldivide, which can be called as eitherx = mldivide(A,b)or, with the help of a little syntactic sugar, using the operator\(e.g.x=A\b).mldivide does not actually calculate the inverse, instead it uses specialised algorithms such as LU decomposition, to calculate \(\mathbf{x}\) at a reduced computational cost and typically with greater accuracy. Indeed, MathWorks are so proud of this function you can buy a t-shirt showing it off:

Fitting a Straight Line between N Points

Consider the case where we want to fit a straight line between three or more points.

\[\begin{bmatrix} y_1 \\ y_2 \\ y_3 \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} x_1 & 1 \\ x_2 & 1 \\ x_3 & 1 \\ \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} m \\ c \end{bmatrix}\]The matrix \(\mathbf{A}\) is no longer square, so it cannot be inverted. Instead, we can perform a pseudo-inverse to get an approximation to the inverse of the matrix, and estimate the vector \(\mathbf{x}\) as

\[\mathbf{x} = \mathbf{A}^{\dagger}\mathbf{y}\]In some special cases, it may be possible to find an exact solution that passes through all points (can you think what would be special about matrix \(\mathbf{A}\) in this case?). However, in most practical situations, there is no exact solution - you cannot draw a single straight line that passes exactly through three or more arbitrary points. Therefore, this methodology finds the “best fit” straight line through your data points. It does this by minimizing the total squared distance between all the points and the line - hence the name “least-squares-fit”.

In MATLAB the pseudo inverse can be calculated using the function pinv. However, this is once again a costly operation and to solve the simultaneous equations we are not actually interested in the value of \(\mathbf{A}^{\dagger}\). Instead, we can once again use the syntax x = A\b to find an estimate of our linear coefficients.

Fitting a Polynomial Line between N Points

A similar process can be achieved for fitting polynomials of higher order. Consider fitting a second-order polynomial (quadratic) to four data points:

\[y = ax^2 + bx + c\]For four data points, we get four equations:

\[\begin{aligned} y_1 &= ax_1^2 + bx_1 + c \\\ y_2 &= ax_2^2 + bx_2 + c \\\ y_3 &= ax_3^2 + bx_3 + c \\\ y_4 &= ax_4^2 + bx_4 + c \end{aligned}\]which can be written in matrix form as:

\[\begin{aligned} \begin{bmatrix} y_1 \\ y_2 \\ y_3 \\ y_4 \end{bmatrix} &= \begin{bmatrix} x_1^2 & x_1 & 1 \\ x_2^2 & x_2 & 1 \\ x_3^2 & x_3 & 1 \\ x_4^2 & x_4 & 1 \\ \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} a \\ b \\ c \end{bmatrix} \\ \mathbf{b} &= \mathbf{A}\mathbf{x} \end{aligned}\]Since we have more data points (4) than unknowns (3), this is again an over-determined system that requires the pseudo-inverse approach to find the best-fit polynomial coefficients.

This process can be extended to fit polynomials of any order. For an nth order polynomial, you would need columns up to \(x^n\) in your matrix, and ideally have more data points than polynomial coefficients to get a good fit.

In MATLAB the function polyfit can also be used to fit an Nth order polynomial to a data set.